Political Graffiti in Athens and Thessaloniki 2007–2020.

Fotos by 381 Crew, NDA Crew, Antifa Shalala, Ore 114, Deck 114.

INFO (dt.)

Wohl in kaum einer anderen Stadt in Europa ist in den letzten Jahren so viel gemalt worden wie in Athen. Viele Sprayerinnen malen am helllichten Tag, ohne nennenswerten Ärger mit der Polizei zu bekommen, weil die Prioritäten derzeit anders gesetzt werden. Seit der Krise in Griechenland hat die Stadt kaum noch finanzielle Mittel, um Graffiti systematisch zu entfernen, auch nicht an repräsentativen öffentlichen Gebäuden. Aus diesem Grund kommen Künstler aus der ganzen Welt in die Stadt, um mit oder ohne die örtlichen Sprayerinnen in den Vierteln zu malen. Eine ähnliche Situation wie in Berlin kurz nach dem Fall der Mauer.

Viel gemalt wird rund um das Exarchia-Viertel, wo es eine große Infrastruktur von Sozialen Zentren und anderen selbstverwalteten Orten gibt, die das abfedern, was der Staat nicht bietet. Die dortige Universität war bis 2019 eine entmilitarisierte Zone, die die Polizei nicht betreten durfte, nachdem dort 1973 ein Aufstand gegen die Militärdiktatur brutal niedergeschlagen worden war. Deshalb ist sie auch heute noch ein wichtiger Ort für politische Gruppen. Insbesondere Graffiti mit Parolen haben in Griechenland eine lange historische Tradition. Sie begleiteten die Konflikte während der Nazi-Okkupation, des Bürgerkriegs und der Militärdiktatur. Seit 1984 gibt es hier auch eine aktive Writer-Szene, die wie anderswo durch die Filmdokumentationen »Wild Style« und »Beat Street« aus den USA einen Anstoß bekam.

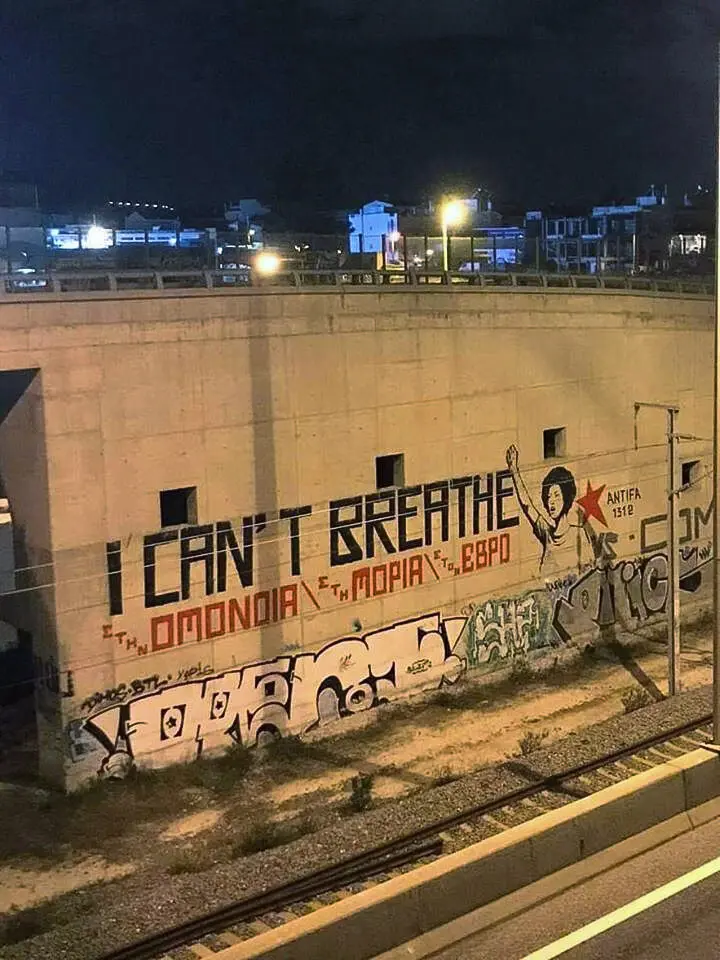

Seit dem 6. Dezember 2008, dem Tag der Ermordung des 15-jährigen Alexis Grigoropoulos durch die Polizei, nahmen die Graffiti nicht nur an den Wänden des alternativen Stadtteils Exarchia explosionsartig zu. Da die Mauern in Athen so gut wie nie gereinigt werden, stellen sie nicht nur eine Momentaufnahme dar, sondern auch eine Art visuelles Archiv der sozialen Konflikte der letzten Jahre.

Der Tod von Alexis löste in ganz Griechenland Revolten aus, die von zahlreichen Writerinnen und Künstlerinnen mit Malaktionen begleitet wurden. Viele von ihnen wurden dadurch zu einem Teil der aufständischen linken und anarchistischen Bewegung. Gleichzeitig ist es wichtig, hervorzuheben, dass viele dieser Writerinnen bzw. Gruppen wie die 381 Crew oder NDA aus Athen, Thessaloniki und anderen Städten bereits von Writerinnen und Gruppen der vorangegangenen Generationen beeinflusst wurden, z. B. von der 114 Crew, die für ihre politischen, abstrakten und experimentellen Aktivitäten mit und jenseits von Graffiti während der 1990er-Jahre bekannt war.

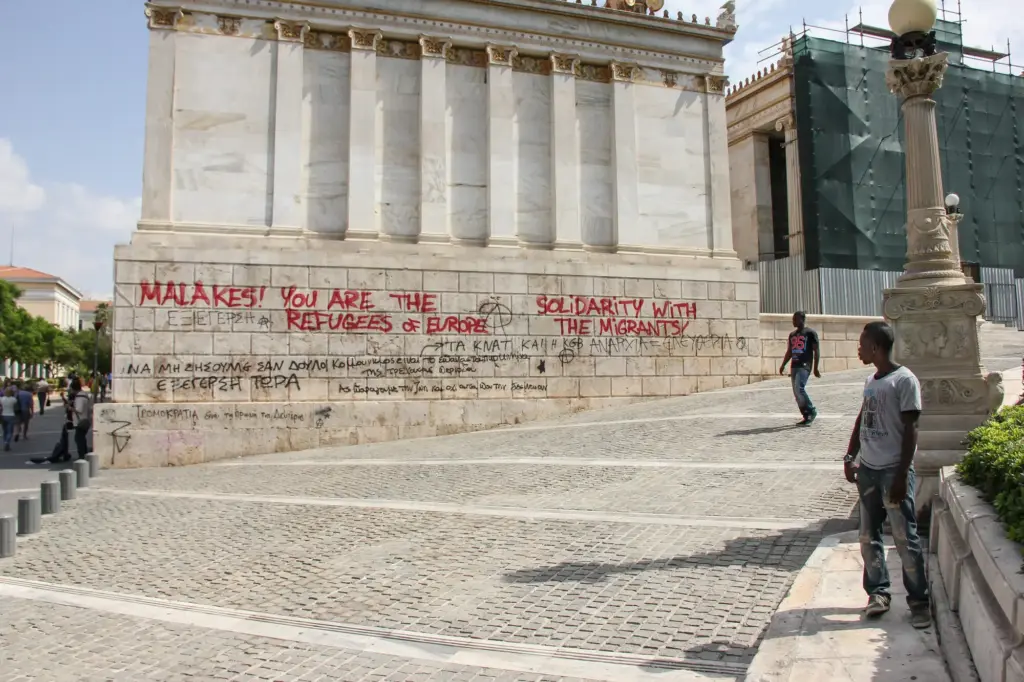

In den Jahren 2011/12 stand die schwere Wirtschaftskrise in Griechenland im Zentrum der medialen Aufmerksamkeit. Viele Zeitungsartikel auf der ganzen Welt zu diesem Thema wurden mit Straßenszenen und Fotos von urbaner Kunst illustriert, z. B. gemalten Protestszenen oder Menschen mit Gasmasken. Ähnlich wie bei den späteren Aufständen in Ägypten wurden die Bilder zu Symbolen der Krise und des sozialen Wandels.

Einige Künstlerinnen waren jedoch frustriert über die Tatsache, dass trotz des enormen Medienrummels und des großen Interesses von Journalistinnen und Wissenschaftler*-

innen an Graffiti und Straßenkunst in Athen das eigentliche Ziel, die griechische Gesellschaft zu mobilisieren und zu verändern, nicht oder nur phasenweise erreicht werden konnte. Auch der Aufschwung einer rassistischen Stimmung und der Wahlerfolg rechtsradikaler Parteien in Griechenland konnte nicht verhindert werden.

Andererseits gelang es den Künstler*innen, eine Sichtweise auf die gesellschaftliche Situation in Griechenland wahrnehmbar zu machen, die sonst in der Öffentlichkeit kaum vorkommt. Sie konterkarierten damit die Erzählung, der zufolge die Bewohner Griechenlands selbst an der Krise schuld seien, da sie über ihre Verhältnisse gelebt hätten und deshalb nun den Gürtel enger schnallen müssten. Jugendarbeitslosigkeit und Massenarmut erscheinen so als Folge eines Fehlverhaltens, gegen die der Staat nichts ausrichten könne. In deutschen Medien wurde in ähnlichem Tonfall geschrieben, dass »wir« nicht verpflichtet seien, für »ihre« Fehler zu bezahlen. Wenn aber Graffitis, Slogans oder Wandbilder die konkreten emotionalen und physischen Folgen der Krise und der Sparmaßnahmen thematisieren, bringen sie in die öffentliche Diskussion, dass es um gemeinsame Probleme geht, die politisch gelöst werden müssen.

Allerdings gab es auch die Befürchtung, dass Kunst und Wandbilder den Krisentourismus für Kulturinteressierte fördern könnten. So gab es auch einen Protest gegen die Kasseler Kunstausstellung documenta, die 2017 unter dem Titel »Von Athen lernen« in die Stadt kam. Es wurde die Frage aufgeworfen, ob nicht letztlich vor allem deutsche Institutionen vom Blick auf Griechenland profitieren würden. Außerdem wurde diskutiert, ob die Gefahr bestehe, dass die prekäre Kulturszene, die sich bisher völlig autonom entwickelt hatte, durch die neuen finanziellen Anreize domestiziert werden könnte.

INFO (engl.)

Hardly any other city in Europe has seen as much painting in recent years as Athens. Many sprayers paint in broad daylight without getting into significant trouble with the police because priorities are currently set differently. Since the crisis in Greece, the city has hardly any financial means to systematically remove graffiti, not even on representative public buildings. For this reason, artists from all over the world come to the city to paint in the neighbourhoods with or without the local sprayers. A similar situation to Berlin shortly after the fall of the Wall.

A lot of painting is going on around the Exarchia neighbourhood, where there is a large infrastructure of social centres and other self-managed places that offer what the state does not provide. The university there was a demilitarised zone until 2019, where police were not allowed to enter after an uprising against the military dictatorship was brutally put down there in 1973. That is why it is still an important place for political groups today. In particular, graffiti with slogans have a long historical tradition in Greece. They accompanied the conflicts during the Nazi occupation, the civil war and the military dictatorship. Since 1984, there has also been an active writer scene here, which, as elsewhere, was given an impetus by the film documentaries “Wild Style” and “Beat Street” from the USA.

Since 6 December 2008, the day 15-year-old Alexis Grigoropoulos was murdered by the police, graffiti has exploded not only on the walls of the alternative district of Exarchia. Since the walls in Athens are hardly ever cleaned, they represent not only a snapshot, but also a kind of visual archive of the social conflicts of recent years.

Alexis’ death triggered revolts all over Greece, which were accompanied by painting actions by numerous writers and artists. Many of them became part of the insurgent left and anarchist movement. At the same time, it is important to point out that many of these writers or groups, such as the 381 Crew or NDA from Athens, Thessaloniki and other cities, were already influenced by writers and groups from previous generations, such as the 114 Crew, which was known for its political, abstract and experimental activities with and beyond graffiti during the 1990s.

In 2011/12, the severe economic crisis in Greece was the focus of media attention worldwide. Many newspaper articles around the world on this topic were illustrated with street scenes and photos of urban art, e.g. painted protest scenes or people wearing gas masks. Similar to the later uprisings in Egypt, the images became symbols of crisis and social change. However, some artists were frustrated by the fact that despite the enormous media hype and the great interest of journalists and academics in graffiti and street art in Athens, the actual goal of mobilising and changing Greek society could not be achieved, or only in phases. The upsurge of racist sentiment and the electoral success of radical right-wing parties in Greece could not be prevented either.

On the other hand, the artists succeeded in making available a perspective on the social situation in Greece that is otherwise rarely seen in public. In this way, they countered the narrative that the inhabitants of Greece themselves were to blame for the crisis because they had lived beyond their means and therefore now had to tighten their belts. Youth unemployment and mass poverty thus appear as the result of misbehaviour against which the state can do nothing. German media wrote in a similar tone that “we” were not obliged to pay for “their” mistakes. But when graffiti, slogans or murals address the concrete emotional and physical consequences of the crisis and austerity measures, they bring into the public discussion the insight that what is at stake are common problems that must be solved politically. However, there were also fears that art and murals could encourage crisis tourism for those interested in culture. There was also a protest against the Kassel art exhibition documenta, which came to the city in 2017 under the title “Learning from Athens”. The question was raised whether German institutions in particular would not ultimately profit from turning to Greece. It was also discussed whether there was a danger that the precarious cultural scene, which had previously developed completely autonomously, could be domesticated by the new financial incentives.